Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum

For four seasons the Los Angeles Dodgers played in what was arguably the most unbalanced ballfield in major league history.

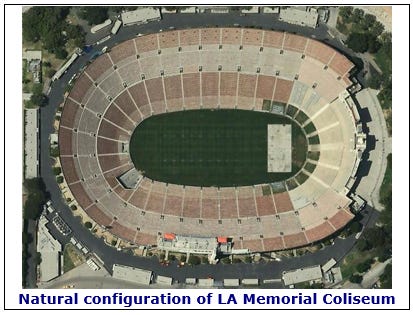

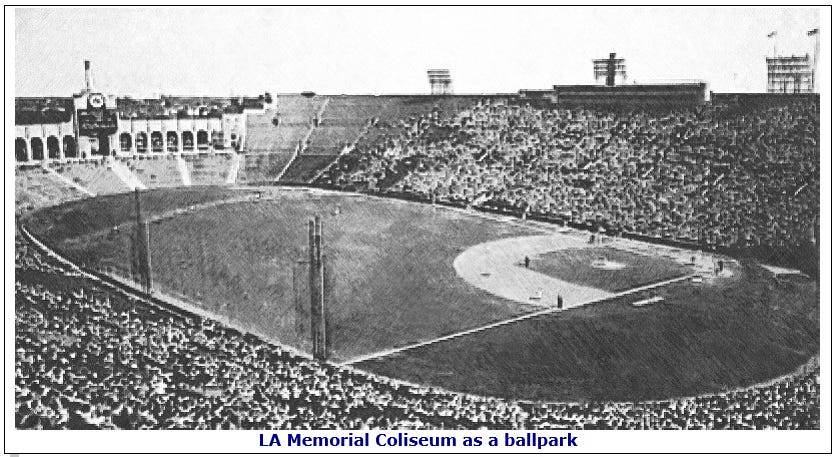

When the Dodgers moved out west in 1958 they needed a place to play while Dodger Stadium was being built, which would take several years because of the lack of basic infrastructure and other prep work that would be needed in Chavez Ravine. Los Angeles was excited about having their first major league club, and the Dodgers wanted their temporary home to be able to accommodate large crowds. That drew their attention to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, which could seat over 90,000 fans. However, trying to cram a baseball field into a facility designed for football and track was challenging to the point of being impossible without accepting absurdities in the layout of the field.

The Dodgers’ first plan was to play weekday games at the original Wrigley Field, which was one of the great minor league parks and had been the long-time home of the Los Angeles Angels in the Pacific Coast League. Then for the larger weekend crowds, the games would be played at Memorial Coliseum. But it was eventually decided that it would be too problematic to have two different home fields, and the Dodgers chose to play all their home games at the Coliseum.

The ball field within the Coliseum had a left field corner that was barely 250 feet from home plate, and so the Dodgers erected a 40-foot tall wire mesh screen to try to stop cheap homers hit toward left field. It didn’t really work. Even members of the press were hitting homers over the screen in an impromptu batting practice. An unusual number of balls were also being hit into the seats in left center as well. The tallest part of the screen stopped 140 feet from the foul line, and then quickly sloped down at a 30 degree angle. The distance where the screen began to shorten was just 320 feet from home plate. At the point where the sloping screen leveled off at a height of eight feet in left-center field, the distance to the fence was still only 348 feet. In contrast, most of the rest of the ballfield had unusually deep fences. The fence line quickly jumped out to 425 feet in CF, got even deeper in right-center field (440) and then ran over to the existing concrete wall that it met at a distance 390 feet from the plate. Only then did the distance taper rapidly down, almost in a straight line, to 301 feet at the right foul line. It was, quite simply, the most unbalanced park in major league history.

Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick was so concerned by all the potential pop-fly homers to left field that he wanted the Dodgers to erect a second fence that would actually be in the stands themselves, roughly 333 feet from the plate. Balls that cleared the first screen but not the second would be ground-rule doubles, and only those that cleared the second fence would be homers. That second fence was nixed by the California building code, and the games had to be played with the single left field fence. In that first season (1958) only 9 homers were hit to center and right field while 182 were hit to left field! Don Zimmer and Charlie Neal, the right-handed hitting double-play combo of the Dodgers, were both small men, weighing 165 pounds. They both set their career-highs in homers in that season and combined for 25 homers in their 443 ABs at the Coliseum. Righty-hitting catcher John Roseboro hit ten homers at the Coliseum and just two on the road. The most homers hit at the Coliseum by a lefty was just six by Hall of Famer Duke Snider — who was coming off five straight 40-homer seasons back in Brooklyn. Snider hit only one more homer at the Coliseum that year than did the righty-hitting pitcher Don Drysdale, who hit his five in just 36 ABs!

In 1959, the Dodgers used an interior fence to shorten the distance of the RF power alley. They also raised the left field screen a couple of feet and fiddled with its height as it extended out to center field. Rather than steadily sloping down, it now declined in height by sections and over a much longer distance than in 1958. That was essentially the park’s configuration for its remaining three seasons (1959-1961) as a big league park. Even with these changes the park still strongly favored left field power-hitters. For those three seasons an average of 145 homers were hit to left field while only 39 were hit to center and right field.

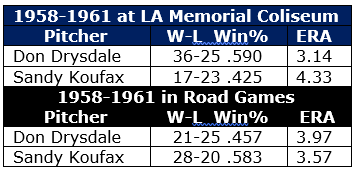

The Dodgers’ two young Hall of Fame pitchers, Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax, were roughly the same age, less than seven months apart. The common belief is that Drysdale developed faster and Koufax was more of a late-bloomer. But that was a ballpark illusion. Because righty hitters were far more dangerous at the Coliseum, the righty Drysdale had an edge in containing them while the lefty Koufax was more vulnerable to their flyballs becoming homers or extra-base hits that struck the tall fence. Drysdale appeared to be the better pitcher in their overall numbers, but the truth is that Koufax was actually the better pitcher when they escaped the Coliseum in their road games.

The ground rules involving the left field screen stated that all of its support apparatus that was not in foul territory — the 60-foot support towers and the associated girders, cables, and wires — were in play just like the wire mesh screen itself, but if a ball actually got trapped in the screen, it was to be a ground-rule double. That seemed clear enough until a crazy and critical play in 1959.

On September 15th, with eleven games left to go, the Giants, Braves, and Dodgers were all battling for the pennant with the Dodgers being the furthest out, two games back. LA was hosting Milwaukee and badly needed a win to stay in the race. The Dodgers had jumped off to a 5-2 lead when in the fifth inning Milwaukee’s Joe Adcock hit a lazy flyball to the short left field wall. He had already cleared the screen for a 2-run homer back in the first inning. This time his flyball struck the support tower on the right side of the screen and it bounced into the screen where it lodged in a section of overlapping mesh from the screen on the center field side.

It was quickly ruled a ground-rule double, but then some youngsters shook the wire screen and the ball fell into the crowd. The call was changed to a home run, but then in conference with all the umpires it was decided to return to the original ruling of a ground-rule double. They decided it could only be a homer if it had immediately rolled out of the screen and fallen into the crowd. Milwaukee manager Fred Haney filed a protest, arguing that the ball had had to clear the screen to be trapped on the side with the crowd, and thus it was already a home run before it was trapped in the screen. He reasoned that in such a case the ground rule would no longer apply.

Adcock did not score from second base and that lost run was critical to deciding the game. The Braves came back to tie the game at 7-7 and then lost 8-7 in the tenth inning. If Adcock’s hit had been ruled a home run rather than a ground-rule double, the Braves likely would have won 8-7 in nine innings. On September 18th, NL President Warren Giles denied the Brave’s protest and the controversial win by the Dodgers became official.

The lost run likely cost the Braves the win, and then the lost win cost Milwaukee the pennant. Instead, the Braves and Dodgers were tied at the end of the season, and Los Angeles won the playoff series over the Braves to take the pennant. If the screen overlap had been properly trimmed, or if Adcock’s hit had immediately rolled out from where it was caught in screen, there likely never would have been a playoff. The Braves would have finished a full game ahead of LA in the regular season to win their third straight pennant.

The freakish ballpark that helped decide the pennant race also made possible the largest crowds in World Series history. Over 92,000 fans turned out for each of the World Series games in LA, with the record crowd for Game 5 totaling 92,706. That never could have happened anywhere but in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

Research Notes

The left field fence in the LA Memorial Coliseum was not the tallest fence in a major league park. Baker Bowl in Philadelphia had a short right field wall that was originally built to be 40 feet tall. In the Live Ball Era there were too many cheap homers being hit over the wall, so they added a wire fence on top of the wall that was reported to be at least 15 feet tall, and some sources say 20 feet tall, making the total height of the wall 55 to 60 feet tall.

The 60-foot support towers in LA were nowhere near to being the tallest objects that were “in play” in a major league park. Several of the older ballparks had flag poles in deep center field that were in play, the tallest of which was the 125-foot flagpole in Tiger Stadium.

While LA Memorial Coliseum heavily favored right-handed power hitters, a lefty batter who developed an opposite field swing could also easily loft balls over the screen as well. The expert at this was lefty Wally Moon, who in his three years with the LA Coliseum as his home field (1959-61) hit 76% of his homers at the Coliseum.

When folks talk about the extremely odd configuration of the ball field at LA Memorial Coliseum, almost all of the focus is put on the outfield fences, but as you can see in the picture below, the distribution of foul territory was also probably the most unbalanced in major league history. The foul territory in play on the 3rd base side was immense, while the foul territory on the first base side was nearly non-existent.

I had never before heard about Adcock's controversial double in 1959. Great detail!